Health Volunteers Overseas: 30 Years of Leveraging International Partnerships to Strengthen Health Worker Capacity

- Health Volunteers Overseas, Washington, DC, United States

Health Volunteers Overseas (HVO) is a United States-based non-profit that collaborates with over 80 universities and health institutions around the world to send volunteer health professionals to provide continuing education, train the trainer courses, professional support, and consultation on academic programs and curricula development. By establishing mutually beneficial partnerships, HVO is able to deliver effective models of collaborative education that contribute sustainable solutions to strengthen health workforce capacity in resource-scarce countries—ultimately improving health outcomes and the quality of life for millions throughout the world. This paper provides an overview of HVO, outlines the role of international partnerships within HVO’s structure, describes the processes used to select partners, and analyzes lessons learned around the key indicators of how to establish and maintain successful international partnerships in education and health worker capacity building.

Introduction

Health Volunteers Overseas (HVO) is a United States-based non-profit that collaborates with over 80 universities and health institutions around the world to send volunteer health professionals to provide continuing education, train the trainer courses, professional support, and consultation on academic programs and curricula development. By establishing mutually beneficial partnerships, HVO is able to deliver effective models of collaborative education that contribute sustainable solutions to strengthen health workforce capacity in resource-scarce countries—ultimately improving health outcomes (Anand and Bärnighausen, 2004; Frenk et al., 2010) and the quality of life for millions throughout the world.

This paper provides an overview of HVO, outlines the role of international partnerships within HVO’s structure, describes the processes used to select partners, and analyzes lessons learned around the key indicators of how to establish and maintain successful international partnerships in education and health worker capacity building.

Background

A critical problem in resource-scarce countries across the globe is the shortage of appropriately trained health-care providers. According to the World Health Organization, the current global health workforce shortage of 7.2 million providers is estimated to increase to 12.9 million by 2035 (Campbell et al., 2013). This disproportionately affects resource-scarce countries, denying basic health care to millions and limiting access to life-saving treatments. Due to limited resources in these countries, not enough health professionals receive training, few have the opportunity for continuing education, and the capability to develop or implement educational programs and curricula is constrained. Additionally, many existing providers choose to emigrate in pursuit of professional advancement opportunities, contributing to the overall shortage of qualified health-care providers in these environments.

Health Volunteers Overseas’ mission reads, “HVO is dedicated to improving the availability and quality of health care through the education, training, and professional development of the health workforce in resource scarce countries.” Since 1986, HVO has worked in resource-scarce countries to educate new health-care providers, provided ongoing professional development to retain and support current providers, advanced the level of practice in accordance with current clinical science, cultivated educators, and enhanced training curricula.

Health Volunteers Overseas’ projects aim to increase intellectual, clinical, and educational capacity of physicians, nurses, physical therapists/rehabilitation specialists, dentists/oral health specialists, and various other allied health professionals and technicians. Activities focus on direct delivery of clinical and didactic training through both formal (degree-based programming, structured continuing education, etc.) and informal (on-the-job training, mentorship, etc.) education, as well as train the trainer courses and faculty development initiatives.

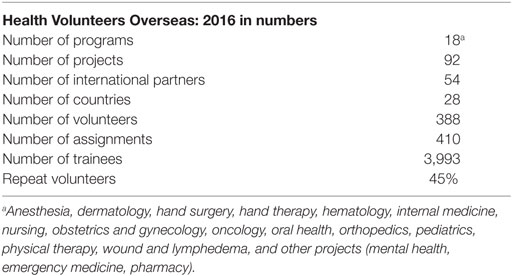

From its founding in 1986 through December 2016, HVO has sent 5,910 volunteers on 10,846 trips to 234 projects. Table 1 provides a summary of HVO’s programs and activities in 2016. A map and details about current programs by country and clinical specialty can be found at www.hvousa.org.

HVO Structure

Health Volunteers Overseas’ projects vary according to the needs of each health institution and country, avoiding a one size fits all approach to project design. However, all of HVO’s projects adhere to certain principles that guide training, including: focus on local diseases and health conditions, use of locally available equipment and supplies, and when possible, train both providers and educators. These principles help foster long-term sustainability of HVO’s activities (Health Volunteers Overseas, 2017a).

Health Volunteers Overseas relies on a short-term volunteer model with average volunteer assignments of 2–4 weeks. Volunteers are senior in stature and experienced practitioners and educators from both clinical and academic backgrounds. Volunteers not only provide the critical man power needed to travel overseas for the direct delivery of education and training but also serve in key leadership roles for each project.

“Program areas” are defined by clinical specialty. Each of HVO’s 18 program areas is overseen by an HVO-appointed Steering Committee, which works with HVO staff to manage all of the projects within a given program area. Each committee consists of 5–8 members who have extensive experience as HVO volunteers and/or in international health-care education within their specialty. Each project has a volunteer project director (PD), primarily in the US, and a volunteer on-site coordinator (OSC), based at the host institution. The PD and OSC are both health-care professionals who work closely with HVO staff to approve and orient volunteers, guide and monitor project activities, and assess impact. The PD and OSC provide critical technical expertise related to their health specialty, which complements HVO’s staff experience in volunteer and project management and international health and development. The OSC officially represents the partner institution in terms of project management and is responsible for overseeing all volunteer activities on the ground. The OSC collaborates with the PD in order to provide the necessary feedback to HVO to promote continuity between volunteers and ensure activities are not duplicative, remain relevant, and maintain a forward progression toward realizing project goals.

Project Lifecycle

Health Volunteers Overseas has developed an organizational Logic Model that defines our program theory and describes the effectiveness of our programs. The model lays out the inputs, outputs, and outcomes of HVO programs at an individual, institutional, and sectoral level with consideration of both HVO and our partner’s contribution to each step. This tool helps guide the organization through the development of new program areas and the lifecycle of each project, ensuring projects align with our mission and capacities.

Project Initiation and Design

Each HVO project actively engages partner institutions throughout the entire project lifecycle from initiation → design → management → and closure. The Guide to Starting New Projects (GTSNPs) is a tool that HVO has developed to ensure all projects are designed using a systematic and consistent methodology (Health Volunteers Overseas, 2017b). Prior to detailing the steps to developing a project, the GTSNP defines the HVO model; lays out basic parameters that must be present to facilitate the development of any HVO project; and defines HVO’s capacities and the scope of educational opportunities that may be considered during project development.

Health Volunteers Overseas’ GTSNP outlines six steps that guide project design.

1. Approve the site assessment. This step ensures that the potential partner’s needs align with HVO’s educational capacities and ensures that basic project parameters are in place. Essential parameters include relative political stability in the country, English language capacity, and local support for the project.

2. Gather background information about the country along with its health care delivery, education system, and the institution requesting volunteers.

3. After adequate background information is collected, an appropriate site assessor is identified to conduct a site assessment. Two priorities of this process include: (a) confirmation that the needs of a potential partner can be addressed through education and training and if so then (b) investigating the educational needs of the potential partner to confirm they align with HVO’s mission and capacities.

4. Initiate the project, which includes: (a) identifying potential trainees, (b) defining the type of training, (c) outlining volunteer qualifications/requirements, (d) determining the types of educational materials, equipment, and/or technology available on site, (e) defining expectations for a successful project both short and long term, and (f) considering logistical issues related to project management and volunteer placement.

5. Develop specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and timed (SMART) goals and objectives collaboratively with the partner/host institution.

6. The site assessor prepares a final report for HVO leadership and the appropriate HVO Steering Committee (a Site Assessment Report Outline is provided in the GTSNP to guide and standardize report preparation).

Once a project has been approved by the respective HVO Steering Committee, HVO staff drafts a preliminary Letter of Agreement (LOA). The LOA is reviewed and approved by both HVO staff and the partnering institution(s) before being finalized for signature. No project activities, marketing, or volunteer recruitment begins until the LOA is signed by all partners.

Project Management

Project management includes the coordination and oversight of ongoing project activities, continuous project monitoring, and annual project evaluation. Project management is a collaborative process between HVO leadership (PD, OSC, and Steering Committee) and HVO staff. Continuous engagement of partner institutions is facilitated through the OSC.

Through a robust system of project monitoring and evaluation, HVO is able to work with our international partners to track progress toward project goals and objectives and determine impact. Annual surveys are conducted as well as occasional on-site evaluations to supplement the ongoing feedback received through continuous communication among the PD, OSC, and staff. Annual analyses and reports are then compiled and presented to enable HVO to remain responsive to our partners needs and adapt project activities and structure in a timely and effective manner.

Project Closure/Redefinition

Multiple scenarios may lead either HVO and/or a partnering institution to determine a project should be closed. The ideal situation is mutual agreement that a project has accomplished its goals. However, external circumstances may lead one or both partners to conclude that the project is no longer viable before the goals are entirely met:

• Basic project parameters are no longer in place—political instability in the host country, loss of partner support, and engagement, etc.

• The host institution’s priorities no longer align with HVO’s mission or educational capacities.

• Leaders change at the host institution.

If there is little to no volunteer activity at a project but opportunities to engage and support the partner institution remain viable, a shift in project status from “active” to “affiliate” may be considered. In this situation, active volunteer recruitment is suspended but HVO continues to support the partner institution according to a redefined set of activities, which may include visits from previous volunteers to the site (active recruitment suspended), efforts to obtain educational materials, facilitation of attendance at educational conferences, or other forms of professional support.

The Role of International Partnerships

Definition of Partnership

A central component of HVO’s educational model is the organization’s reliance on international partnerships to achieve its mission. The justification for adopting the partnership approach relies on the belief that intra and cross sector collaboration can maximize impact and promote sustainability when attempting to address complex global health issues. Historically, international partnerships have not been built around the principle of equity in decision-making, mutual collaboration, or shared responsibility (Lewis, 1998). Instead, they often employed a hierarchical approach where power imbalances led to unevenness of influence between partners (Ashman, 2001), typically disadvantaging low and middle income country partners and leading to unsustainable interventions (Freeman, 2015).

While defining the specific terms of individual partnerships can be quite nuanced, HVO has found that the most successful model of partnership relies on a “collaborative relationship between two or more parties based on trust, equality, and mutual understanding for the achievement of a specific goal. Partnerships involve risks as well as benefits, making shared accountability critical” (World Health Organization, 2009). For over 30 years, HVO has relied on this collaborative model of partnership to ensure the success of individual projects and sustainability of interventions.

Health Volunteers Overseas uses the term “partner” to refer to institutions of other countries that co-sign with HVO a formal LOA for a project and/or host HVO project activities as defined in the LOA. Over 80% of HVO’s partners (also referred to as host institutions) are universities or teaching hospitals but partners may also include other non-profit organizations or smaller health clinics. These institutions may be private, government, or non-profit entities. Over the last three decades, HVO has worked with at least 107 unique partners on 234 projects spanning 60 countries.

Lessons Learned/Key Indicators of a Successful Partnership

Instilling a culture of cooperation throughout each level of the organization is foundational to sustaining a successful and inclusive model of partnership. This requires a structured and strategic approach to partnership that must be cultivated by executive leadership and actively incorporated into the organization’s practices and procedures.

Over 30 years, HVO has continually refined its model by learning from failure and adapting to change. Every 5 years, HVO undergoes a strategic planning process that involves the HVO Board of Directors, staff, leadership, volunteers, and other stakeholders. This process has been invaluable over the years by enabling the organization to respond to the evolving needs of our partners and the global health community at large. Three decades of experience has also enabled the organization to refine the indicators of a successful partnership.

Key indicators of a successful partnership:

1. Mutual goal setting (Wildridge et al., 2004; Leffers and Mitchell, 2011). When host institutions actively engage in defining project goals, objectives, and activities, both partners are invested in realizing project outcomes. This applies not only in the project design phase but is necessary throughout the project life-cycle as goals and objectives may evolve over time. Ongoing collaboration on project goal setting helps ensure project activities and interventions continuously align with host institution priorities and instill a sense of project ownership and responsibility on the part of the host institution, thereby increasing the likelihood of sustainable change.

2. Honest and open communication (Tennyson, 2003; Wildridge et al., 2004). Establishing and maintaining effective communication instills confidence that partners are moving toward the same goals. Language and cultural barriers can often present communication challenges, especially when working with international partners. HVO has found that partners may be hesitant to provide honest or constructive feedback on the project due to concerns it may negatively impact the relationship or project status. It is important to acknowledge these challenges exist and integrate strategies to mitigate potential misunderstandings and facilitate honest communication. In this regard, HVO has developed orientation materials and provides guidance to volunteers and leadership to address cross-cultural communication challenges and enhance their oral and written communication. Further, HVO works with the host institution to encourage constructive feedback through ongoing project monitoring and evaluation. Facilitating honest and open feedback relies on HVO framing the discussion appropriately and demonstrating that constructive feedback is welcomed, non-threatening and critical to the success of the project.

3. Equity (Tennyson, 2003). Initiating and sustaining a partnership requires a dedication of time, staff, and resources. HVO recognizes that each partner will provide different types of resources to a project based on their unique capacities and available resources. While resource contributions often cannot be calculated or equated in financial terms, each partner’s contributions are essential to project success. During the project design phase, each partner’s commitments and projected contributions are outlined and, then, included in the LOA, which requires annual reassessment as external variables may influence available resources. Ultimately, seeking equity within a partnership recognizes each partner’s right to be “at the table,” regardless of an imbalance in resource contribution.

4. Mutual benefit (Tennyson, 2003). Often, partners are independently accountable to stakeholders external to the immediate partnership. Considering this, it is critical to identify where strategic, organizational priorities align when designing a project. HVO’s Logic Model was designed with this key tenet of successful partnerships in mind and clearly maps out broad areas of alignment that have been identified.

In addition to institutional/organizational benefits, mutual benefit is realized at the level of the individual trainee and volunteer. HVO orients volunteers through phone calls and documents, including the HVO KnowNet (a password-protected tool, open to all HVO members and colleagues at our project sites around the world that serves to orient volunteers preparing for overseas assignments and promote educational exchange) prior to their departure for a site. The benefits to the trainees are outlined in the project objectives and result in changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes as a result of the teaching and training provided. HVO has also documented a positive personal and professional impact on volunteers as reported in post-trip surveys, including broadened professional perspectives, increased cross-cultural competency, strengthened professional networks, and increased clinical confidence.

5. Active partner engagement throughout the project lifecycle (Afsana et al., 2009). While one partner may be responsible for a larger percentage of project oversight and ongoing management, each partner must be kept up to date on project activities and engaged in decision-making. It is important that expectations and roles are strategically and realistically mapped out during the project development phase and solidified in the LOA. Ultimately, HVO is a guest within the host country and institution where each project operates. This perspective is foundational to our approach and active engagement of our partners throughout the project life-cycle reflects this philosophy.

6. Flexibility (Wildridge et al., 2004). Partnerships require flexibility to evolve and transform over time. This is especially true in global health where priorities and needs may shift as a result of changing health demographics, donor trends, local resources, leadership, or the strategic mission or capacities of one or both partners. Through mutual and ongoing project monitoring, evaluation, and effective communication, HVO is able to work with our partners to continuously re-assess if the nature of the partnership and/or the goals of a project need to be updated. In Bhutan, this flexibility has enabled our partnership with Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH) to sustain for over 25 years. HVO initiated its partnership with JDWNRH in 1991 to begin training in orthopedics as there was no Bhutanese orthopedist or formal orthopedic training program in Bhutan at that time. Since 1991, HVO has been able to adapt to meet local needs to establish a physician assistance program (1993–2005), followed by an orthopedic technician program (2006), orthopedic internships (2014), and most recently, an orthopedic residency program (2017). Since 2001, HVO’s partnership with JDWNRH has also broadened in scope to include projects in physical therapy, anesthesia, mental health, emergency medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and oncology.

7. Clearly define leadership roles (Wildridge et al., 2004). As mentioned previously, HVO’s model relies on volunteers at all levels of the organization, including leadership. HVO has defined a broad set of roles and responsibilities for all PDs and OSCs. However, HVO has learned that each partner has a unique set of capacities and, therefore, the exact roles and responsibilities for the OSC (and partner institution more broadly) are defined during the project design phase and stated in the LOA for each project.

8. Local champion. Identifying a local champion at a host institution helps maintain project momentum and often guides the evolution of the partnership (Leffers and Mitchell, 2011). HVO has found a local champion may or may not have an official leadership role within the HVO project or the host institution. However, they have a demonstrated ability and willingness to leverage their personal or professional power and go beyond task related deliverables that may be defined in a formal leadership role. Common skills and traits of a local champion include the ability to motivate, inspire, negotiate, be resourceful and liaise with all parties to effectively and efficiently move the project forward.

Conclusion

Over 30 years, HVO has been able to identify key indicators of a successful international partnership and integrate strategies into our internal structure and processes that promote these key principles. However, it is important for organizations such as HVO to recognize each partnership is unique and as the global health environment and priorities of our partners evolve, models of international partnership must adapt to stay relevant. HVO remains committed to learning and refining our philosophy and internal processes around equitable international partnerships to promote integrated and sustainable contributions to strengthening health worker capacity.

Author Contributions

AP and NK conceived the paper jointly; AP prepared the first draft; NK reviewed and refined the draft. Both authors edited and approved the final submission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Afsana, K., Habte, D., Hatfield, J., Murphy, J., and Neufeld, V. (2009). Partnership Assessment Toolkit. Ottawa: Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research.

Anand, S., and Bärnighausen, T. (2004). Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet 364, 1603–1609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17313-3

Ashman, D. (2001). Strengthening North-South partnerships for sustainable development. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect. Q. 30, 74–98. doi:10.1177/0899764001301004

Campbell, J., Dussault, G., Buchan, J., Pozo-Martin, F., Guerra Arias, M., Leone, C., et al. (2013). A Universal Truth: No Health without a Workforce. Forum Report, Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, Brazil. Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization.

Freeman, C. (2015). Can We Address Imbalances of Power in Cross-Sector Partnerships? Available at: https://www.devex.com/news/can-we-address-imbalances-of-power-in-cross-sector-partnerships-86405

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., et al. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376, 1923–1958. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

Health Volunteers Overseas. (2017a). The Guide to Starting New Projects. Washington, DC: Health Volunteers Overseas.

Health Volunteers Overseas. (2017b). Our Mission, Vision, Values. Available at: https://hvousa.org/whoweare/our-mission/

Leffers, J., and Mitchell, E. (2011). Conceptual model for partnership and sustainability in global health. Public Health Nurs. 28, 91–102. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00892.x

Lewis, D. (1998). Development NGOs and the challenge of partnership: changing relations between North and South. Soc. Policy Adm. 32, 501–512. doi:10.1111/1467-9515.00111

Tennyson, R. (2003). “The partnering toolbook,” in International Business Leaders Forum (IBLF), the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), International Atomic Energy Association, UNDP, ed. E. Wood (New York: UNDP), 1–55.

Wildridge, V., Childs, S., Cawthra, L., and Madge, B. (2004). How to create successful partnerships – a review of the literature. Health Info. Libr. J. 21, 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1740-3324.2004.00497.x

World Health Organization. (2009). Building a Working Definition of Partnership: African Partnerships for Patient Safety (APPS). Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/apps/definition/en/; http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/apps/resources/defining_partnerships-apps.pdf

Keywords: global health, health workforce, partnership, Health Volunteers Overseas, health worker capacity building

Citation: Pinner A and Kelly NA (2017) Health Volunteers Overseas: 30 Years of Leveraging International Partnerships to Strengthen Health Worker Capacity. Front. Educ. 2:30. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00030

Received: 11 May 2017; Accepted: 16 June 2017;

Published: 04 July 2017

Edited by:

Allen C. Meadors, The Global Leadership Group, United StatesReviewed by:

Roger Glenn Brown, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, United StatesJohn Denley Lentz, Private Practice in Periodontics (Retired), United States

Timothy Lynn Taylor, Indian Health Service (Retired), United States

Copyright: © 2017 Pinner and Kelly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: April Pinner, a.pinner@hvousa.org;

Nancy A. Kelly, n.kelly@hvousa.org

April Pinner

April Pinner Nancy A. Kelly

Nancy A. Kelly